Overview

In this unit, we will be introducing two seemingly separate topics that actually have a deep connection:

Both of these are vital tools in computer science, and we will see some examples that demonstrate this idea. We will also be using these ideas directly in the next unit.

Part 1: Mathematical Induction

To start off, let’s talk about the induction proof technique. This is the last main proof technique that we had left out from Unit 1 because it really deserves that much attention. This is one of the most handy tools that we use in order to prove statements we care about, and in this section we will present two variants of this technique:

Revisiting An Example: The Arithmetic Series

To show you what I mean, let’s revisit an example that I had mentioned when introducing and motivating proofs in the first place:

Can we show that ?

(Recall that .)

You might notice that based on the tools we’ve covered so far, you might be tempted to start a proof by saying:

Let be arbitrarily chosen.

And after that point, you’ll need to show that . But even to me, this sounds difficult. If anything, perhaps we were all told this fact in high school so we can take it to be true. But what if I told you there was a way to prove it?

Here’s the high-level strategy:

- (Base case) Firstly, we will prove that when , the left-hand side is the same right-hand side, i.e., .

- (Inductive case) Secondly, we will assume that for some , the left-hand side is the same as the right-hand side, then prove that for , the left-hand side is still the same as the right-hand side.

Let me show you what I mean, then after that explain why this makes sense.

Proof

- (Base case) Let . Then . [Basic algebra]

- (Inductive case) Assume that for some , where , we have .

- [Basic algebra]

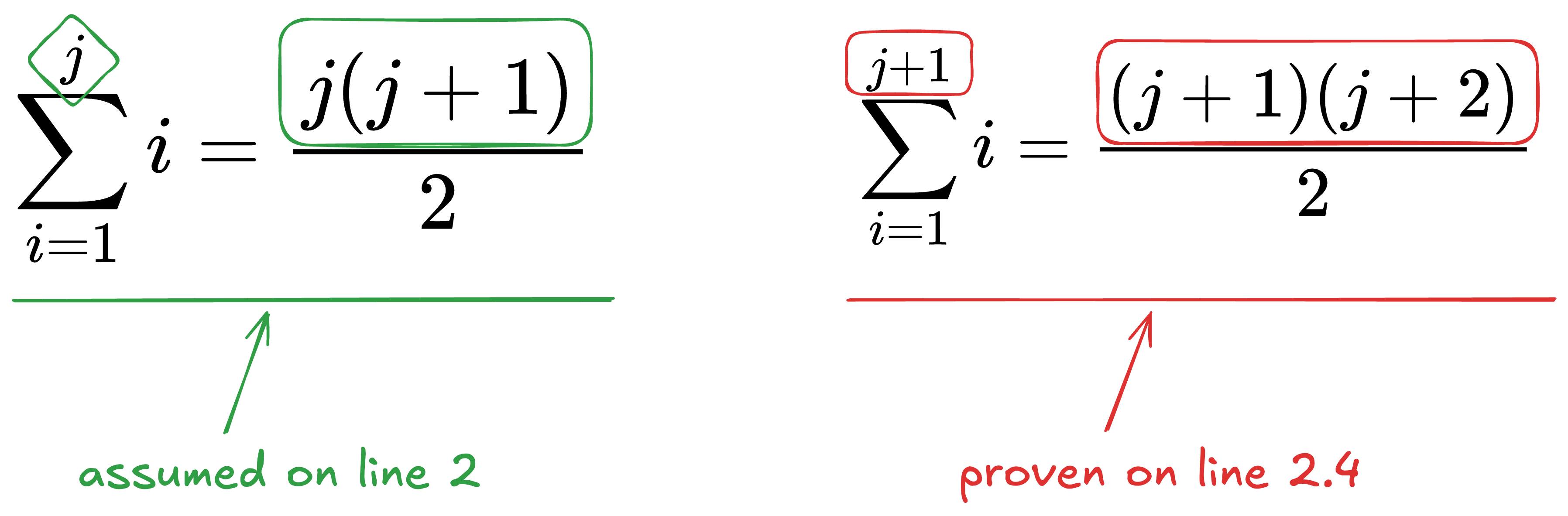

- [By assumption on line 2]

- [Basic algebra]

- [Basic algebra, from lines 2.1, 2.2, 2.3]

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

There are quite a few features of this proof, and let’s talk about the most important one first: let’s focus on what happened on line 2.

We assumed the equality works for some , and we need to prove that the equality works for .

What the induction principle does is the following: given a statement (in our example, states that ):

- If you have proven the statement for a base case (in our example, when ), and

- You have proven the statement for the inductive case (in our example, we assumed that is true, then showed that is true),

Then the induction principle allows you to conclude that , the statement is true. In other words, the statement is true no matter the natural number we give it.

Formally:

Definition: Induction rule

Let be a statement about some .

Suppose that we have proven that is true. Also, suppose that we have proven the implication that for some , . (This second statement is also sometimes known as the inductive hypothesis.)

Then, we may conclude that .

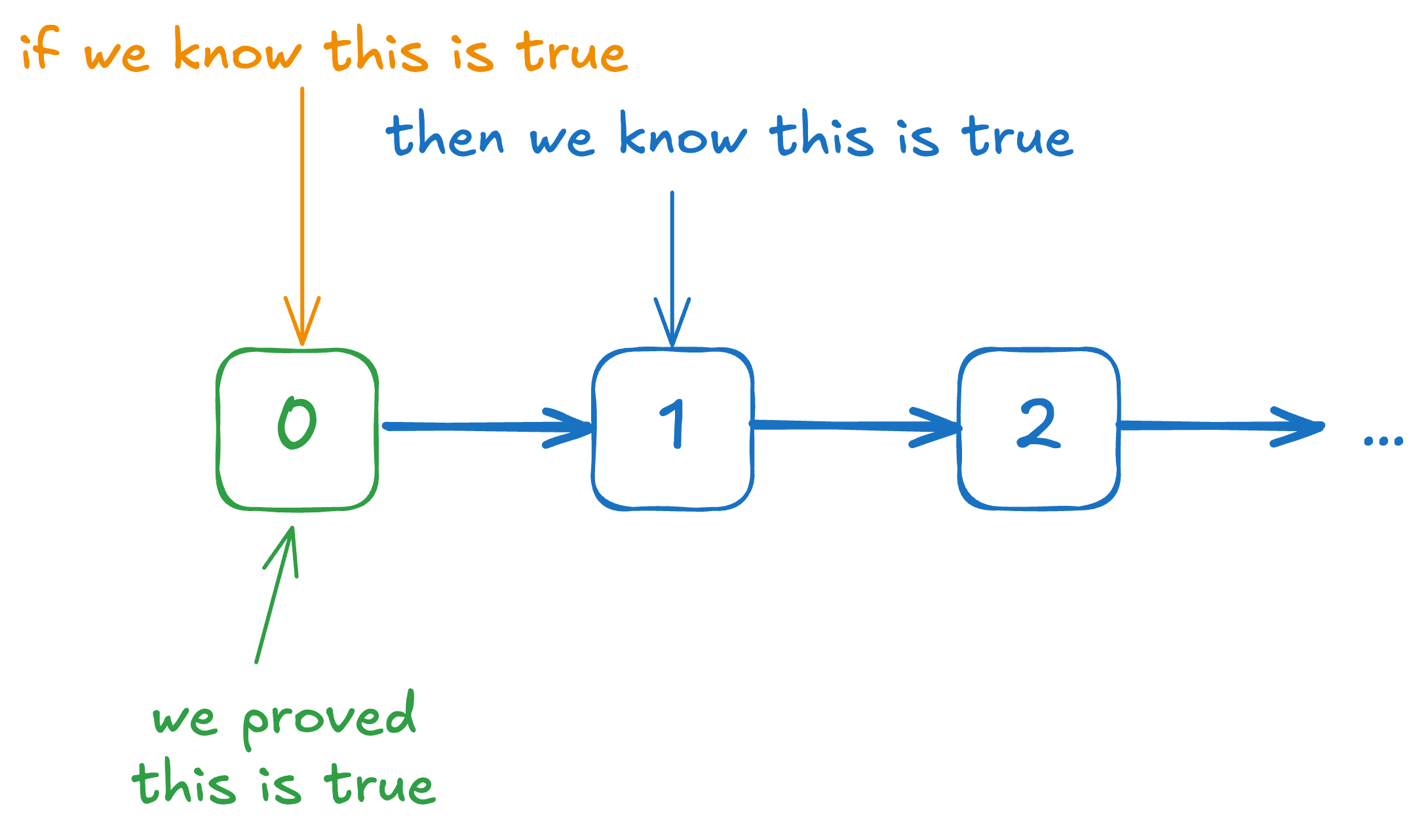

Why does this work? Here’s the intuition:

We know that the statement works when . We also know that if the statement works for , it also works for . So we can conclude that it also works for (by modus ponens on the inductive hypothesis). Similarly, we know that if the statement works for , it also works for . Since we do know that it works for , we can now also happily conclude that it also works for . And so on and so forth.

Proof By Induction Template

In general, to prove some statement , we use the following idea:

- Prove .

- Prove that if is true, then is also true.

Or, more formally:

- Prove .

- Prove that .

In the very first example we gave just now, the statement was defined to be .

One more example: Bernoulli’s inequality

Let’s do one more example, here’s an inequality we sometimes use in computer science:

Theorem

Let such that . Then, for all ,

To be clear, from a high-level overview, we want to show that:

- The statement is true when .

- Assuming that the statement is true when , then the statement is also true when .

Once we do these two things, we can conclude that for all ,

Proof

- Let such that .

- (Base case) Let . Then . [Basic algebra]

- (Inductive case) Assume that for some , where , we have .

- [Basic algebra]

- [By assumption on line 3]

- [Basic algebra]

- [Combining lines 3.1, 3.2, 3.3]

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

Again, pay special attention to line 3.2, we used the inductive hypothesis that in order to prove that:

What happens: Base case not proven

Let’s talk about a common issue that happens in induction proofs. It is quite common that people forget to include base cases in their proofs, and they end up thinking some statement is true, because they thought they had a proof for it.

Here’s an example, let’s say we wanted to prove that:

For all , is odd.

Or a little more mathematically:

Consider the following faulty proof:

Faulty Proof

- (Inductive case) Assume that for some , where , we have .

- [Basic algebra]

- , for some [By assumption on line 1, and existential instantiation of line 1]

- [Basic algebra]

- [Combining lines 1.1, 1.2, 1.3]

- [Existential generalisation on line 1.4]

Have we actually proven the statement? Well, no! In fact, the exact opposite is true: for all , is actually even, not odd.

Hence, it’s very important to remember to cover the base case.

What happens: Base case is not 0

At some point you might come across statements that look something like this:

In English, this states that:

For all natural numbers such that , .

(To be clear, .)

Let’s test this for a few values to see when it starts being true:

| 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 3 | 8 | 6 |

| 4 | 16 | 24 |

| 5 | 32 | 120 |

Notice how seems to overtake only around onwards. So how do we prove this? We change the base case!

Proof Attempt

- (Base case) Let . Then, .

- (Inductive case) Assume that for some , where , we have .

- [Basic algebra]

- [By assumption on line 2]

- [Basic algebra, since when ]

- [Combining lines 2.1, 2.2, 2.3]

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

Again, pay attention to the how the base case has changed on line 1 in order to do our proof. Basically, we are claiming that only from onwards, and not saying anything about when .

Proof By Strong Induction Template

Let’s modify the “proof by induction” template a little bit more: instead of assuming for just a single and trying to prove the statement for , let’s tweak this instead to the following:

Strong Induction Template

- Prove for some base case value .

- Prove that assuming , then is also true.

But why would we do this? Here’s an example:

Example Using Strong Induction:

Let’s say that we lived in a country, where the only denominations are the -dollar and the -dollar bills. Your friend, coming from Singapore, is doubtful that such a system would work. Let’s convince them that we can use -dollar and -dollar denominations to make any dollar value that is $ or larger.

This seems true right? For example:

- $ itself uses two of the -dollar bills (i.e., )

- $ uses one -dollar bill and one -dollar bill (i.e., )

- $ uses two -dollar bills (i.e., )

Formally, we want to prove the following statement:

Again, take note that we wish to prove this for from onwards, which hints to us that our base case should start from . Pay special attention to the fact it is onwards (i.e., not necessarily just itself). This will become very important later. (Subtle foreshadowing…)

So let’s look at a proof sketch:

Proof Sketch

- (Base case) Let . Then, .

- (Inductive case) Let , and assume that , we have that .

- Since , and we assumed that for all , it was true that , then we can say that . [By assumption on line 2]

- Let be such that . [Existential instantiation on line 2.1]

- Then, . [Basic algebra]

- [Existential generalisation on line 2.3]

- Therefore, , . [Principle of mathematical induction]

Okay, so the proof looks reasonable. What if I said there’s an issue?

Let’s think about —can we actually use only -dollar notes and -dollar notes to make the dollar amount of $? We actually can’t!

So where did we go wrong in our proof? It was our assumption. We assumed that for all values , we can express using -dollar and -dollar notes. So in our proof that it was possible for , we had to assume that it was true for . Did we prove this? No we didn’t, and that was the issue.

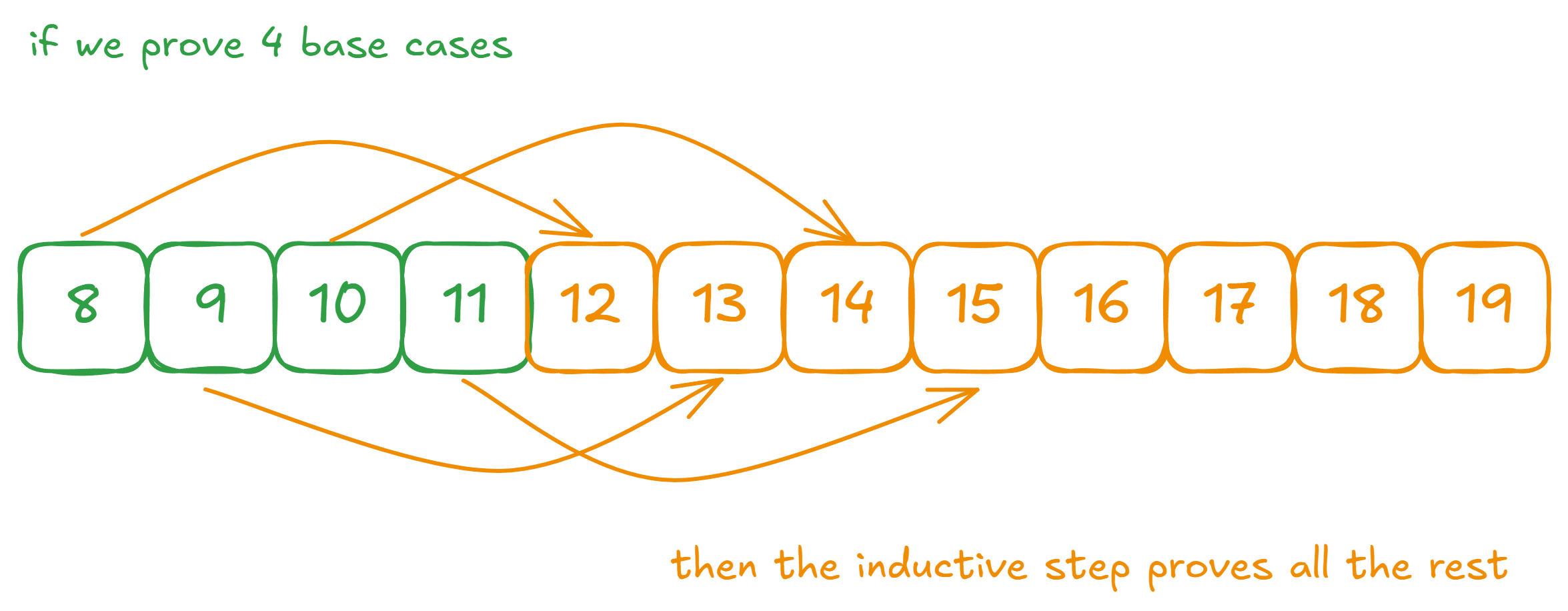

So let’s look back at our proof and see how we can fix this. To prove it for , we needed to assume it for . Since in our base case, we only proved it for , this means we can only know for sure that values like , , , , and so on can be expressed using -dollar and -dollar denominations.

So how do we prove this for all numbers? Notice that if (emphasis on if) in our base cases, we also proved it for starting values , , and , then we can prove it for all numbers, because:

- If we know it works for , we know it works for .

- If we know it works for , then it works for .

- If it works for , it works for .

- If it works for , then it works for .

And we can keep repeating this to prove it for all the numbers from onwards. Pictorially speaking, it looks like this:

Then why are we convinced that the statements for , , and are true? Similarly, because if we know it’s true for , , and , then we can say that for , , and as well.

Okay, let’s take a step back. We just said that we cannot do this for . This means that we actually cannot say “All dollar values from onwards can be made using -dollar and -dollar denominations.”

Okay, but what if I said that we could actually do this for dollar values onwards? Let’s see the proof of this. This time the proof is correct. We have also shortened the proof a little bit, so all the important parts remain, but it is less verbose than in the previous weeks.

Proof

- (Base cases) We need to prove the statement for , , and .

- (Inductive case) Let , assume that for , .

- Since and , .

- Let , be such that . [Existential instantiation on line 2]

- [Basic algebra]

- Since , . [Basic algebra]

- [Existential generalisation on lines 2.2, 2.3, 2.4]

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

Pay special attention to the following:

- There are now base cases, because in the inductive proof, we are taking exactly steps back.

- In our inductive case, we start from , which is above the base case.

- We also, for induction, assume that the statement we wish to prove holds true for values from up until .

Before we round off this section, let’s provide a more formal definition of strong induction:

Definition: Strong induction rule

Let be a statement about some .

Suppose that we have proven that is true for all .

Also, suppose that we have proven the implication that for some ,

Then, we may conclude that .

Strong induction is especially handy when it comes to analysing recurrences. We will see more examples after the second topic on recurrences in this unit, and next week.

Part 2: Recurrences

Let’s talk about another concept that is commonly used in computer science: recurrences.

A Motivating Example: Binary Search

Let’s start with a motivating example. You might have seen this snippet of code before for an algorithm called binary search that looks for a particular key in an array of elements:

def binary_search(arr, left, right, key):

if left + 1 === right:

return arr[left] === key

mid = (right + left) // 2

if arr[mid] <= key:

return binary_search(arr, mid, right, key)

else:

return binary_search(arr, low, mid, key)How do we analyse the running time of such an algorithm? While this is an advanced topic that we will not cover too comprehensively in this module, I think it serves as a good example of why we need to know about recurrences and the proof by induction—it help us analyse and understand recursive algorithms (among many other concepts in computer science).

Recurrence Relations

Put simply, a recurrence relation is a way to describe a sequence of numbers recursively.

Example 1: A simple recurrence

For example, we say is a recurrence defined as:

Notice that . But what about ? Well . Since we also know that , this means that .

Perhaps you have spotted the pattern— is actually just , as long as is a natural number that is at least . Perhaps this is obvious, but even something like this can be proven by induction! In fact, this baby example is the perfect practice question!

Try proving the following:

Theorem

Let be defined as above. Then .

Admittedly, our very first example of a recurrence was probably not very exciting. But I think it is a simple example to point at some features of recurrences. Pay attention to how this example of recurrence defines using 2 cases:

- When , is defined to be . This is our base case. It does not refer to any other values of .

- When , is defined to be . This is our inductive case. Notice how refers to .

For a recurrence to make sense, it needs to have at least one base case, and the inductive cases have to eventually reach the base case(s). For example, to compute , we need to know what is. To know what is, we need to know what is. is a base case, so we definitely know what it is. Then, we know what is, and in turn, what is.

Let’s look at more advanced examples of recurrences to show you more interesting concepts we can solve.

Example 2: Factorials

Recall that (pronounced ” factorial”) is defined to be:

For example:

Can we make a recurrence such that ? It’s yet another good example you might want to think about before reading how to define it. Think about what the base case should be, and what the inductive case should be.

Anyway, here’s the recurrence!

Solution

Let’s run through an example:

Also, here’s a proof that the recurrence matches what we want.

Theorem

As expected, we are going to do this by induction.

Proof

- (Base case) Let . Then . [By definition of the recurrence]

- (Inductive case) Assume that for some , we have .

- [Definition of ]

- [By assumption on line 2]

- [Basic algebra]

- [Combining lines 2.1, 2.2, 2.3]

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

Example 3: Climbing stairs

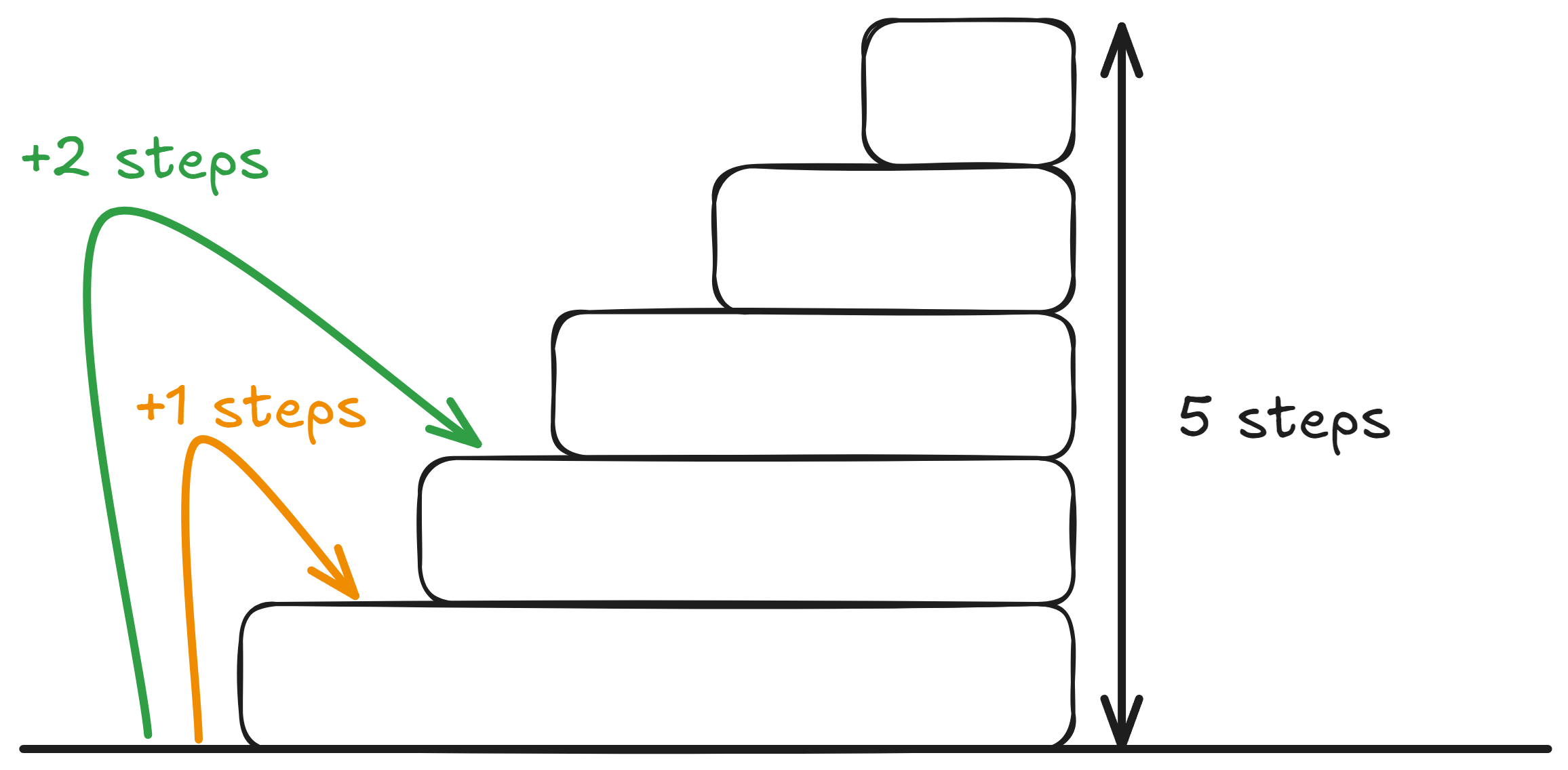

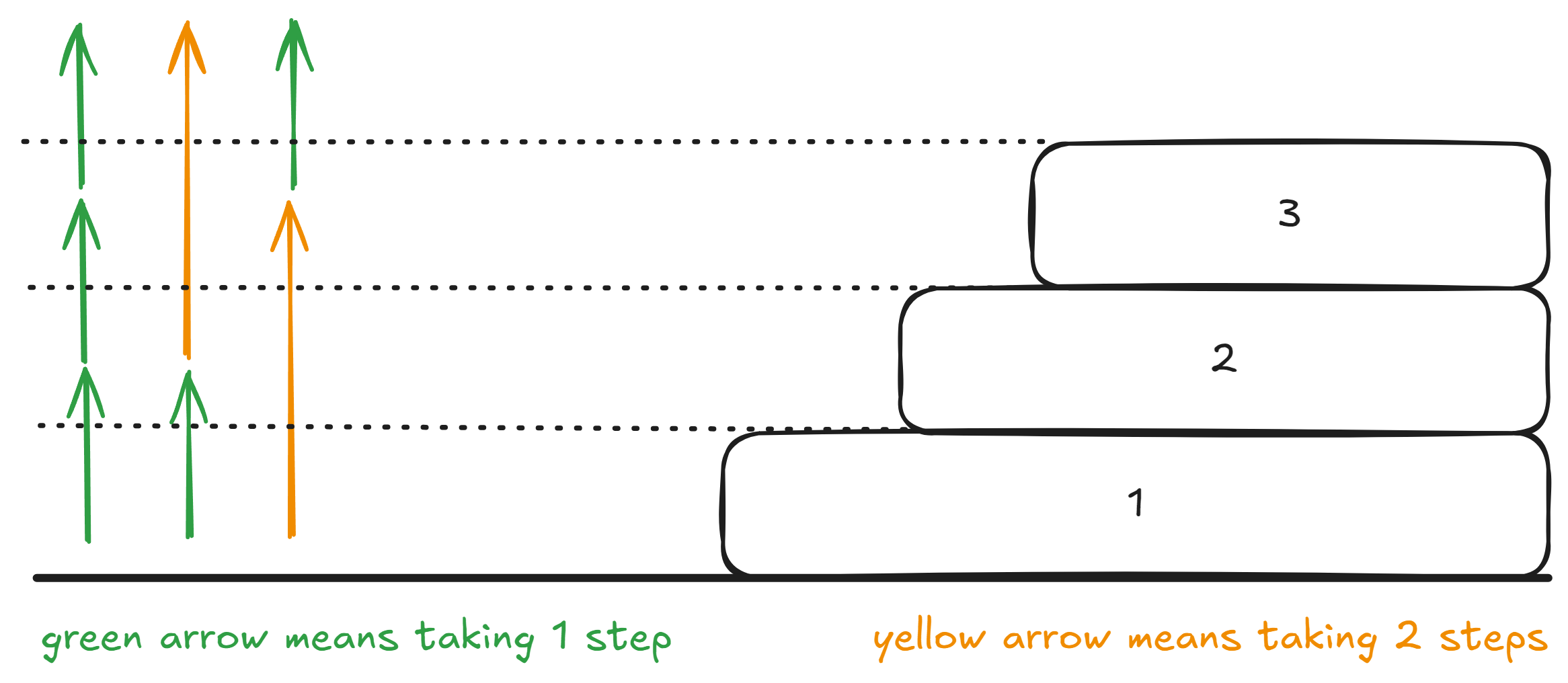

Let’s say that there are a flight a flight of stairs with steps. We want to reach the top of the stairs, but we can only either take step or steps at a time. How many possible ways are there to reach the top?

For example, if we had steps, then the number of ways would be , because:

- Either we only take single steps.

- We take a single step, then a double step.

- We take a double step, and then a single step.

More generally, what is a recurrence such that tells us how many ways there are to climb stairs with steps? To solve this, we should think about a few base cases first.

For , there is only one way: take a single step. For , there are two ways: take single steps, or take double step.

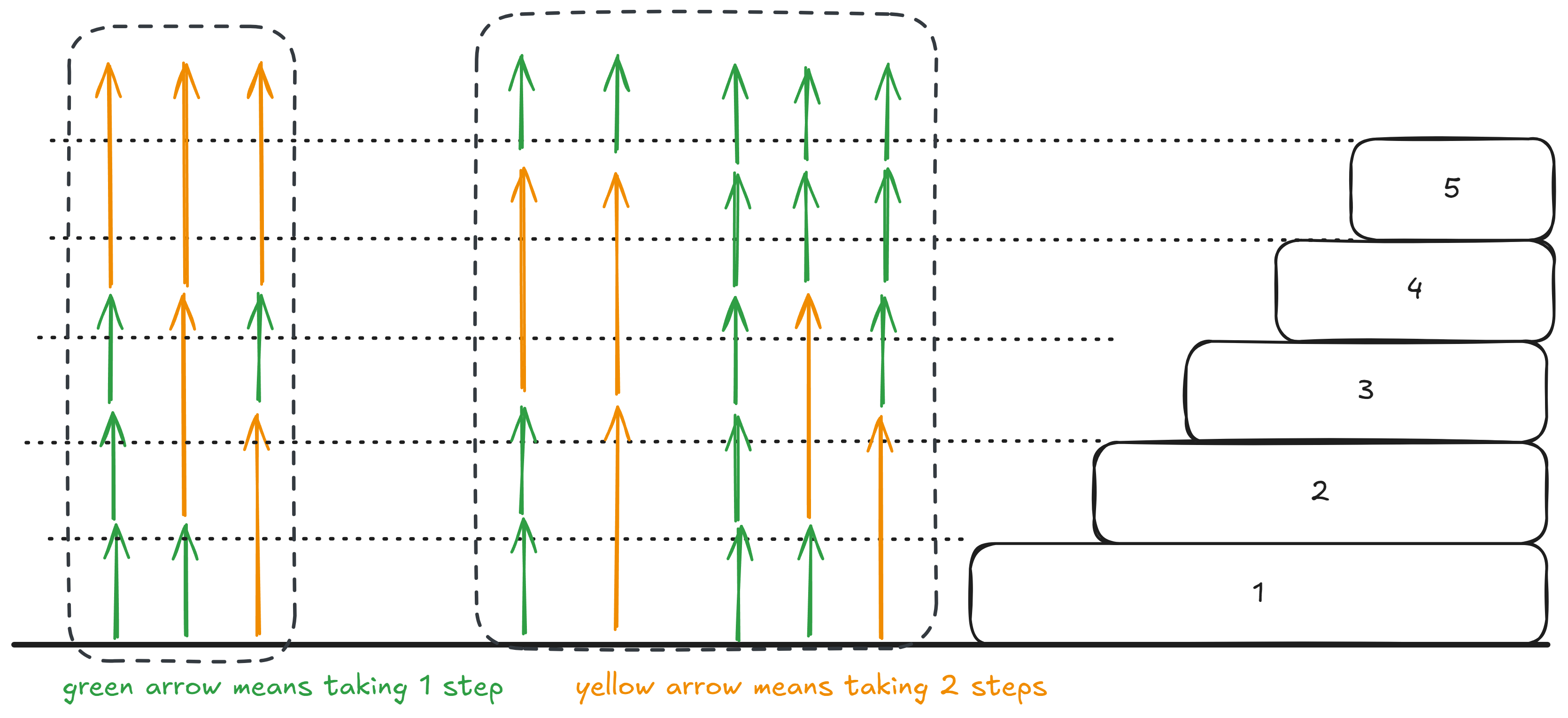

What about some general ? Think about it this way: to reach the step, we just need to count the number of ways to reach the step, and then take a single step after that to reach the step. Alternatively, we could count the number of ways to reach the step, and then take a double step after that to reach the step.

So the recurrence looks like this:

Pay attention to how this time around, we have two base cases: and . What happens if we only had a single base case of ? Are there any issues with this?

Answer

If we didn’t have a base case for , then is not defined, i.e., we cannot compute the value of .

Think about it: how many ways are there to climb steps? Well, that’s simply (the number of ways you reach the step) plus (the number of ways you reach the step). Why? Because for each way you reach the third step, you can take a double step at the end. For each way you reach the step, you can take a single step at the end.

Notice that in the left box, that is essentially (the number of ways to reach the step), and in the right box, that is actually (the number of ways to reach the step). Notice that we need to take a double step after the reaching the step, and we need to take a single step after reaching the step.

Therefore, is really just the addition of those two counts!

You can even write a python program that does this for you:

def stair_climbing(n):

if n === 1:

return 1

if n === 2:

return 2

return stair_climbing(n - 1) + stair_climbing(n - 2)You might notice that for large enough values of , the program is substantially slow. This is something we will talk about in the tutorial and the next unit!

Example 4: Binary search

Let’s end by tying recurrences back to the motivating example of binary search. In the grand scheme of things, recurrences are a tool used in program/algorithm analysis, among many things. So how about we ask ourselves, how many array accesses does the binary search program make?

Let’s look at the code again:

def binary_search(arr, left, right, key):

if left === right:

return arr[left] === key

mid = (right + left) // 2

if arr[mid] <= key:

return binary_search(arr, mid + 1, right, key)

else:

return binary_search(arr, low, mid, key)

binary_search(arr, 0, len(arr) - 1, key)How do we begin? Well let’s look at the base case of our algorithm, it’s basically saying when the sub-array that we care about has only one element left, then we access arr[left] and compare it against our key. So when our sub-array is of size , only one array access is made.

What about in general? Well then our array is split into two sub-arrays: , and .

In either case, if we started with an array of length , we are going to recurse on an array of length at most .

So if we let be the number of array accesses our binary search makes on an array of length , we can then say that:

How do we analyse this recurrence? This is something we will study in detail in the next unit. But for now, can we get a sense of its long-term behaviour?

We want to say this algorithm does not need to access “too many” elements in the array—only about elements. How do we do this?

Let’s prove that .

Proof

- (Base case) Let . Then .

- (Inductive case) Let , and assume that for all , we have .

- Since , then . Therefore, our assumption applies to . [Basic algebra]

- Then, we have the following inequality:

- [Principle of mathematical induction]

So what does this mean? This means that we know for arrays of size onwards, then the function is upper bounded by some curve. This is a hint to us that we are not using many array accesses, and thus the program is actually efficient!