Overview

In this unit, we will introduce graph theory, the final novel, and perhaps unfamiliar mathematical topic. Graph theory is super useful in modelling ideas. We use graph theory in many ways in computer science, either for re-stating problems in a way that computers can understand, or to analyse and count quantities that we care about.

The goal of this unit is to get you familiarised with basic graph terminology and basic theorems about graphs. So in this unit, there will be far less proving, and a lot more of just building mathematical vocabulary. This is mostly because graphs are quite application focused in computer science, and mostly interesting in their own right from a mathematical perspective. Thus, actually talking about anything interesting should be done from the perspective of the topics using them, like algorithms, or natural language processing, or AI.

Why Graph Theory?

Modelling Problems

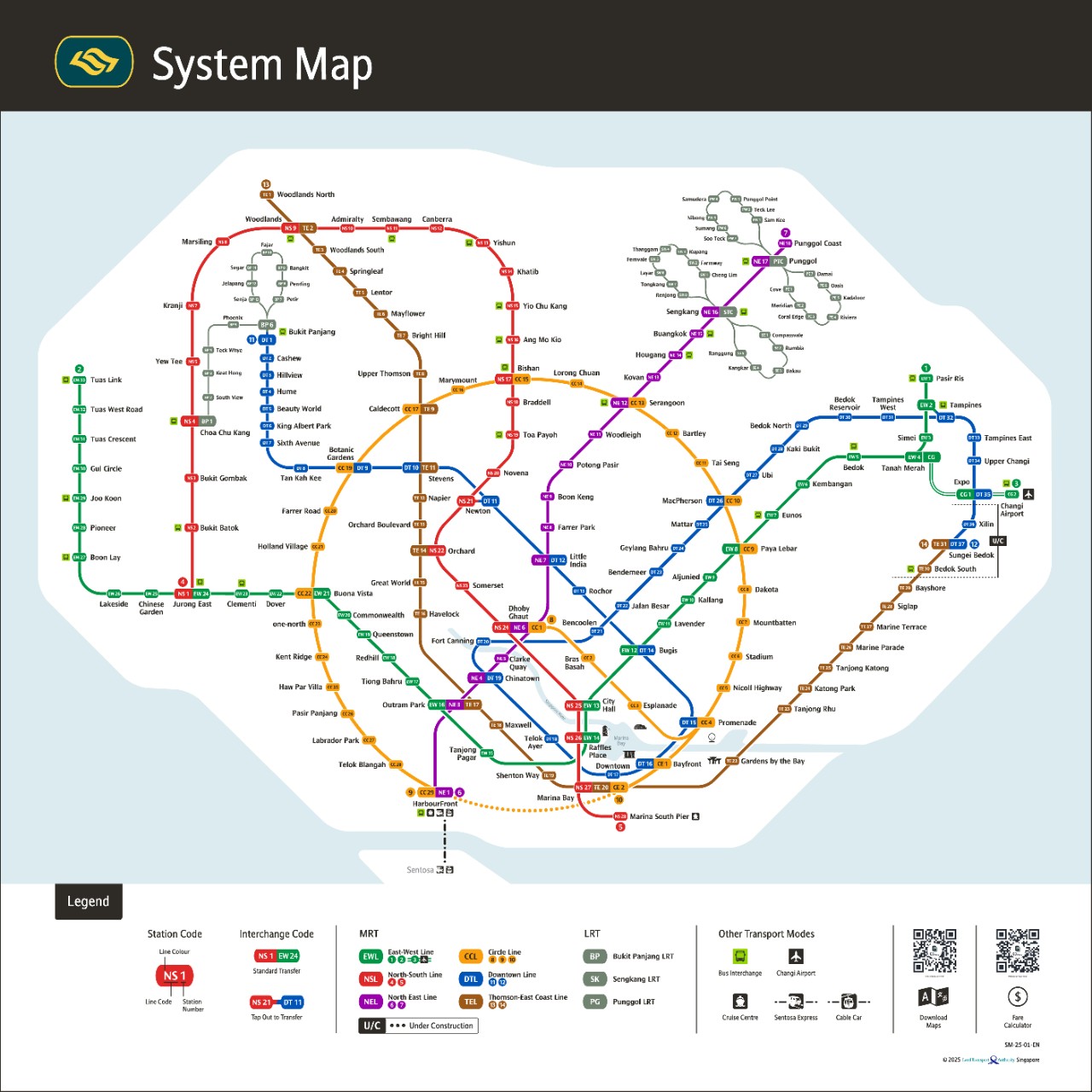

Have you ever wondered how Google maps knows how to route you from point A to point B?

How does it take a system like the MRT map, and figure out how to get you from e.g. Clementi station to Kent ridge station?

Or how about in video games, how do non-playing characters know how to move towards you? Here’s an example video showing pathfinding in action in a video game.

How about your network packets? How does your computer know how to send their requests to the various servers it does? Sure you could say “I type in google.com and my computer figures it out for me”. But someone had to design that solution, and it comes by first modelling a real-life problem, as a graph.

Graph theory is a great way to model problems, models that computers can understand, and models that we can build solutions on.

Analysing Data Structures

The other reason, as you will see when you come around to algorithms and data structures, is that graph theory helps us understand basic data structures too! So the combinatorial aspect of data structures is useful as well.

Basic Definitions

Graph

A graph is defined a pair of sets , where:

-

is a set of vertices or nodes.

-

is a set of edges connecting pairs of vertices. Think of .

A graph is a subgraph of if: and .

So for example, we might have a set of 4 vertices. These vertices might represent locations, like MRT stations, or network nodes, like routers.

An edge is a pair, like , which indicates a connection from to . So here’s an example edge set . Pictorially, it should look like this:

In fact, it’s very common to look at graphs pictorially to get a better sense of what is going on.

Common Types of Graphs

Graphs come in many shapes and forms, and we would like to refer to special cases of them. Let us go through some examples. But in summary, here are 4 types of graphs that we can have.

-

Undirected Graph: Edges have no direction.

-

Directed Graph (Digraph): Edges have a direction (represented as arrows).

-

Simple Graph: A graph without loops or multiple edges between the same vertices.

-

Multigraph: Allows multiple edges between two vertices.

Undirected Graphs

Undirected graphs are when the edge connections are 2-way.

So for example, with , we can have edges . Here, when we draw the graph, we omit the arrowheads.

Directed Graphs

Directed graphs are when the edge connections are 1-way.

So for example, with , we can have edges . Here, when we draw the graph, we include the arrowheads. Now, take note that we can still have 2-way connections like between and . But to do so, we need to have 2 edges. One from to , and one from to .

Simple Graphs

Directed graphs are where there are no: (1) Self-loops, (2) no duplicate edges.

So for example, with , we can have edges . Notice we cannot have the to edge, because that is a self-loop.

Multi-Graphs

Multigraphs are graphs that can have duplicate edges, or self-loops.

So for example, with , we can have edges . Notice here we have duplicate edges from to , and we have a self-loop to .

Some Terminology About Graphs

Degree

The degree of a vertex is number of times appears as an endpoint of some edge. This is applicable for undirected graphs.

So for example:

Node has degree , has degree , has degree , and has degree . It might be a little unintuitive why node has degree . But that is because appears as an endpoint twice! Even if it’s on the same edge.

In a directed graph on the other hand, there is an in-degree and an out-degree.

Node has out-degree , has out-degree , has out-degree , and has out-degree . On the other hand, every node in this example, has in-degree .

Path

A path is a sequence of vertices where each consecutive pair of vertices is connected by an edge. And we do not repeat vertices in a path.

For example, a path is something like a sequence .

Connectivity

A graph is connected if there is a path between every pair of vertices. So based on the previous example, we know that and are connected. We can similarly argue that is connected to or , and so on.

Connected Components

In an undirected graph, a connected component is a maximal set of vertices such that all pairs of vertices is connected by a path.

So again, using the previous example, we know that is a connected component. If we used any smaller set of vertices like , then it is not maximal: We could have added even more nodes and it would still be connected. On the other hand, something like is not a connected component because there exists pairs of vertices that are not connected.

Cycle

A cycle is a path where the starting vertex is also the ending vertex and no edges or vertices are repeated (other than the starting and ending vertex).

So again, using the previous example, we know that is a cycle. Only the first and last vertex in our path has repeated.

Special Types of Graphs

Let’s shift our attention to these 3 special kinds of graphs: trees, bipartite graphs, and complete graphs.

Trees

A graph is a tree is a connected graph with no cycles. You can alternatively think of a tree as a graph such that:

- All nodes are connected to each other;

- .

So here’s an example:

If you want, count the nodes, and count the edges, you’ll realise that we have nodes, and exactly edges. Furthermore, all the nodes can reach each other.

Typically (but not always), we will also specify what is the root of the tree. In the drawn example above, is our root node. Now that we have established a root node, we can start talking about the other important names have for the special case of trees. When heading “away” from the root, we traverse from parents to children. For example, we can head “away” from by moving from node to node . So is called the parent of . Similarly, this means that is the child of . has two children: and . You might want to think about how every node only has at most parent, and never or more.

Also, when we reach a node that has no children, that node is called a leaf. So in this tree, we have leaves: and . Any node that has children is called an internal node. So here, are internal nodes.

Lastly, if every node in a given tree has at most children, we say the tree is -ary. For example, a tree where each node has at most children is called a 2-ary or binary tree.

Bipartite Graph

A graph is bipartite if we can take its vertices and divide them into two disjoint sets and , such that every edge connects a vertex across the two sets and , and never within the sets themselves. So let’s do an example:

The graph on the left is bipartite. Why? Put nodes in set , and nodes in set . Then the only edges are crossing between set and . To make it obvious, we can shift the nodes around a little bit so that the nodes in are on the left, and nodes in are on the right.

Also if you’re curious, could we have done and instead? The answer is yes!

What about this graph instead? Is it bipartite?

You might notice no matter how hard you try to form the sets and , there’s always an edge that is either within set or within set . Why can’t we do it? The idea is that this an odd length cycle. So if a graph every contains an odd length cycle, it is not bipartite. If the graph does not contain any odd length cycles (i.e. we can never make one), then it is bipartite.

Complete Graph

Lastly, let’s talk about complete graphs. An undirected graph is complete, if every pair of nodes has an edge between them.

So for example, for 5 nodes, this is what the graph looks like.

On the other hand, this is what the complete graph looks like for nodes.

Complement Graphs

On the topic of complete graphs: we can now talk about the complement of a graph.

So given a graph , the complement of G is written as , and is such that has the same set of nodes, but if was an edge in , it is not an edge in . And if was not an edge in then is an edge in .

Here’s an example:

here has nodes, and notice since is an edge in , and are not connected in . Similarly, since and are not connected in , they are connected in .

One thing you might want to take note is that if we union the edges from and , we get back the complete graph.

Theorems and Proofs

Okay, let’s do a few theorems about graphs. I have chosen the 3 most useful ones that I know.

The handshake lemma

Claim: The sum of the degrees of all vertices of an undirected graph is twice the number of edges. In other words:

Let’s see an example of this:

Notice that we have edges, and . Wow! But why does it work?

Intuition:

Each edge contributes exactly 2 to the total sum. Once for adding to the degree of node , then once again adding to the degree of node . So it adds to our sum twice. So each edge contributes a total of to the sum. Since each edge contributes , this means the sum is .

Number of Edges in a Complete Graph

The number of edges in a complete graph with vertices is:

So again you might have noticed, for example, a graph with nodes has edges.

There are two ways to prove this fact for a general graph:

Proof (via Combinatorics):

Think about it, every pair of vertices that we can form from the set , makes an edge. So this means that the number of edges is the same as the number of possible pairings. This happens to be:

Short and sweet!

Proof (via Handshake Lemma):

There is another way that actually uses what we’ve learned here today. Think about it this way, in a complete graph with vertices, every node has exactly other nodes that it is connected to. Because of that, every node has degree exactly . So, via the handshake lemma:

Which means:

Number of Nodes in a -ary tree

Lastly, this fact is super userful, combinatorially in CS: The number of nodes in a -ary tree of height .

Given a graph that is a -ary rooted tree of height , then:

- The minimum number of nodes in the tree is

- The maximum number of nodes in the tree is

So here’s an example if a -ary (or ternary) tree, of height . At minimum we can have nodes. And at maximum we can have nodes. But what about in general? Here’s the idea:

We need nodes at least to go from a root to a leaf node that is hops away. So the minimum is .

To hit the maximum, every internal node will have all children, and every leaf node again, must have children. So the total nodes we have are:

But what about in general for a -ary tree? Well just swap out the for a .

Pigeonhole Principle

Lastly, let’s talk about the pigeonhole principle. This is a little bit of an oddball topic but it’s very common to also cover it during combinatorics and graphs. It would be remiss if we did not at least mention it. Pigeonhole principle feels like stating the obvious, but it can be used to great effect.

Simply put: If we have pigeons, and pigeonholes, and each pigeon wants to nest in a pigeonhole, then there exists at least one pigeonhole that has at least pigeons that are nesting in it.

This sounds a little obvious, for example with pigeons and holes, there is definitely a hole with at least pigeons. But here’s an example statement we could possible argue with it.

There are at least 2 people with the same number of strands of hair on their head in Singapore.

Why is this true? Think about it this way, there are around 6 million people in Singapore. And the average human has around 100,000 strands of hair on their head. So it’s reasonable to say it’s possibly impossible for a human to have a million strands of hair.

So we make 1 million possible pigeonholes, and each person is a pigeon, we assign a person to the pigeonhole if they had strands of hair on their head. Since there are million people but only million pigeonholes, there must be at least people who have the same number of strands of hair on their head.