How to submit:

- Submit before actual tutorial time for it to be graded. There are 2 ways to do this:

- There is a submission box on Canvas for you to submit your document. Either .docx, .pdf, or a picture of your written solutions are acceptable as long as we can read your attempts.

- Submit your written attempts in-person during our tutorial.

- Official due date for submission : 01-Apr-2025, 23:59 or during tutorial itself.

Collaboration Policy:

- You may discuss high-level ideas with your classmates or friends. You should list your collaborators if you do so.

- Do not share your solutions.

- ChatGPT (and other LLMs) are not allowed.

- Your submission must be of your own write-up.

Late Policy:

- < 1 week after submission deadline: 50% penalty

- < 2 weeks after submission deadline: 75% penalty

- No submissions after 2 weeks.

Overview

This tutorial gives practice questions to be discussed during the relevant tutorial in person. This particular tutorial sheet corresponds to Unit 6 and Unit 7. It is recommended to either watch the lectures or read the notes for each respective parts before attempting the tutorial sheet.

- Questions 1 through 2 are related to combinatorics.

- Questions 3 through 6 are related to graph theory.

- Question 8 is related to pigeonhole principle.

After week 9’s content, you should be able to attempt questions 1 through 2. Questions 1 is graded for participation.

After week 10’s content, you should be able to attempt questions 2 through 7. Question 5 is graded for participation.

That said, we encourage you to try all the questions, this way when you come for tutorial we can best make use of your time since you can either verify your solutions, or understand the discussions when our tutors go through the solutions.

Question 1 [Graded for Participation]:

Let’s say that we want to build a password system that only accepts:

- Lowercase letters (a-z); there are 26 possible choices

- Uppercase letters (A-Z); there are 26 possible choices

- Numbers (0-9); there are 10 possible choices

We are going to try to count how many possible password there are, depending on different rules that the system will allow.

Sub-question 1:

Let’s say the password system says:

Any password must be of length and .

If this is the only requirement, how many possible passwords are there? You need not compute the actual value, you can leave your answer in the form of a summation if need be.

Solution

For passwords of length , there are choices for each character, giving us possible passwords. Similarly, for passwords of length , there are possible passwords of that length.

Hence, there are passwords in total.

Sub-question 2:

Let’s say the password system says:

Any password must be of length and , and must be alphanumeric. I.e. At least one alphabet (either uppercase or lowercase), and at least one number.

If this is the requirement, how many possible passwords are there? You need not compute the actual value, you can leave your answer in the form of a summation if need be.

Hint: Can we make use of ideas from Subtracting Cases somehow?

Solution

Without restrictions, there are a total of passwords (from sub-question 1).

Subtracting the number of passwords for the following cases leaves us with the required answer:

- Case 1: Passwords that contain only alphabets and no numbers

- Case 2: Passwords that contain only numbers and no alphabets

For case 1, there are now only choices per character, so there are such passwords. For case 2, there are now only choices per character, so there are such passwords.

Finally, subtracting these two values from the total gives us as the answer.

Sub-question 3:

Let’s say the password system says:

Any password must be of length exactly , and must alternate numbers and characters.

So a password like “a1b2c3d4” or a password like “1m9j8s7h” is allowed. But something like “aa1b3d0p” is not allowed because we have adjacent characters.

If this is the requirement, how many possible passwords are there? You need not compute the actual value, you can leave your answer in the form of a summation if need be.

Solution

There are two cases:

- Case 1: Starts with an alphabet

- Case 2: Starts with a number

Logically, these two values are equal since we are only swapping the order in which the alphabets and numbers appear. This means we only need to calculate the value of one of the cases.

For case 1, there are choices for each of the alphabets and choices for each of the numbers, giving us a total of possible passwords. Case 2 gives us the same value.

Hence, the total number of possible passwords is .

Sub-question 4:

Let’s say the password system says:

Any password must be of length exactly , and must not repeat any numbers and characters.

So a password like “a1b2c3d4” or a password like “1m9j8s7h” is allowed. But something like “a1b3d0pa” is not allowed because “a” has been repeated.

If this is the requirement, how many possible passwords are there? You need not compute the actual value, you can leave your answer in the form of a summation if need be.

Solution

We are now choosing any set of characters from the pool of alphanumeric characters given, which ensures that we do not choose any single character twice. However, after choosing the characters, we need to permute them.

Hence, there are a total of possible passwords.

Sub-question 5:

Let’s say the password system says:

Any password must be of length exactly , must be alphabetical, and the password letters must be sorted, and each letter must only appear once.

So a passwords like “adgkwxyz” or “abcdefgh” are allowed, because they are sorted in alphabetical order. But something like “bajoweaz” is not allowed.

If this is the requirement, how many possible passwords are there? You need not compute the actual value, you can leave your answer in the form of a summation if need be.

Solution

We choose a set of characters from the pool of alphabetical characters, which ensures that we do not choose any single character twice. Since for any particular set, there is only one permutation in which the letters are in alphabetical order, we do not need to account for their permutations.

This gives us a total of possible passwords.

Question 2:

Sub-question 1:

Let’s say we wanted to arrange 5 people around a table. How many possible ways are there for us to arrange them? In general, how many possible ways are there for us to arrange people?

To be clear, if we had people, then it doesn’t matter where they sit, only the relative ordering matters.

Solution

Let’s consider a simpler case of people, , and . Writing each valid seating arrangement in a line instead of around a circle, we might have a particular seating arrangement as such: where counting is done clockwise.

Observe that this represents the same seating arrangement as and . In a way, we can “shift” the people by a single position each time to generate a different way of representing the same seating arrangement, of which there are .

Hence, for people, we have permutations (in a row), and for each actual valid seating arrangement, we have triple-counted them within these permutations. Hence, we need to divide by to get the actual number of seating arrangements.

Applying this concept for the case of people, we have permutations (in a row), and each valid seating arrangement is counted five times, so we divide this number by to get the correct number of seating arrangements. This gives us a count of .

More generally, for people, there are ways to seat them around a circular table.

Sub-question 2:

Again let’s say we wanted to arrange people around a table, but an arrangement and its anti-clockwise arrangement are considered the same. How many arrangements do we have now?

Solution

Now, each of the arrangements from sub-question 1 is double-counted since its anti-clockwise counterpart was previously treated as a distinct seating arrangement. Hence, we now only have distinct seating arrangements.

Question 3:

Among a group of 7 people, is it possible that every person is friends with exactly only 2 other people? Is it possible that every person is friends with exactly 5 other people?

Solution

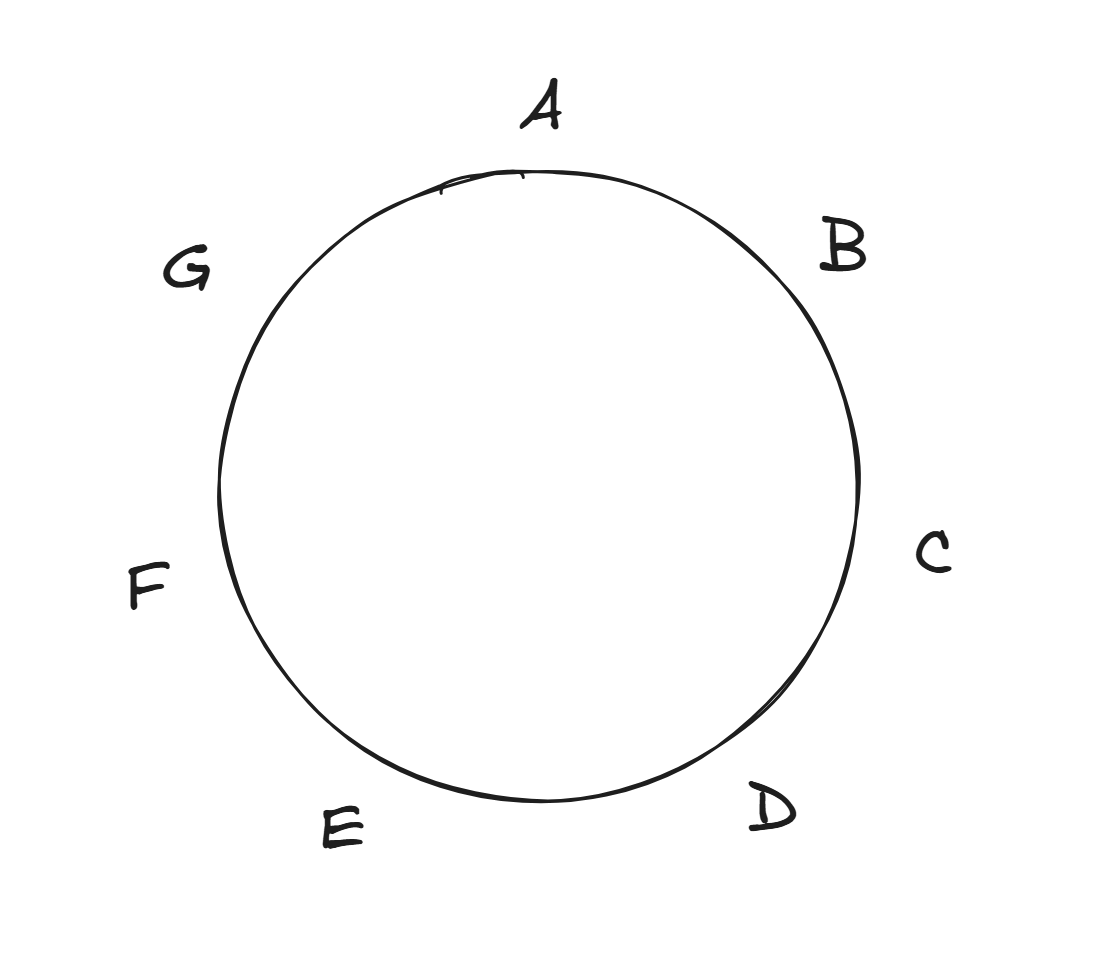

For the first part, it is possible for each person to be friends with exactly other people. Imagine all 7 people form a circle, they are friends with the people that are right next to them. In the image below, consider if A is friends with B and G, B is friend with A and C, so on and so forth.

For the second part, it is impossible for such a scenario to occur. Consider the people as vertices of a graph , where two people are linked (have an edge between them) if they are friends. If each person is friends with exactly people, then .

From the handshake lemma, we know that . Since all nodes have degree , this means .

This means that the degree of must be , which is odd. Since the total degree of any graph must be even, this scenario cannot occur as always has to be an even number.

Question 4:

Given a graph that has edges, how many edges does have?

Solution

The maximum number of edges possible is , where there exists an edge between any two vertices in .

Hence, if has edges, then must have edges.

Question 5 [Graded for Participation]:

Given a graph that is a full -ary tree of height . How many nodes does it have? How many edges does it have? How many leaves does it have?

Solution

From the lecture notes, we know that a full -ary tree of height has node at level 0, nodes at level 1, nodes at level 2, and so on. Hence, the number of nodes in the tree is

Observe that each node has edge to its parent, except for the root node (which has no parents). Hence, the number of edges in the tree is

The number of leaves is simply the number of nodes at the level, which is .

Question 6:

Given a complete graph on nodes, how many cycles can we possibly make?

Solution

Let’s think about what happens if we had nodes first. Let’s call them . So the only possible cycle is . Think of going forwards as the same as going backwards. This is actually, again, a circular arrangement! Just like in Question 3.

Another example, let’s say we had nodes, let’s call them . Then there are actually possible cycles we can make (if we didn’t care about clock-wise vs anti-clock-wise):

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

- .

Notice here for example that going from can be seen as the same as .

So we can divide this by to get a total of possible cycles.

Every cycle requires at least nodes, with each -cycle involving exactly of the nodes. Hence, the total number of cycles that can be constructed for a graph with nodes is

For graphs with nodes, the number of cycles that can be made is .

Question 7:

Let’s say that there was a tournament with teams. A match happens when different teams play against each other (A team cannot play against itself). This means a team can participate in any number of matches from to inclusive.

Show that there will always been 2 teams that have played the exact same number of matches.

Solution

We use the pigeonhole principle, where the “pigeons” are the teams and the “pigeonholes” are the number of matches played.

Proof:

- There are two cases: either there is a team that has played exactly games, or there is no such team that has played exactly games.

- Case 1: There is a team that has played exactly games.

- Since that team has played everyone else, there cannot be a team that has played exactly games.

- Hence, there are possible number of games played by each team, ranging from to .

- Since there are teams and only possible number of games played, there must be teams that have played the same number of games. [By pigeonhole principle]

- Case 2: No team has played exactly games.

- Now, there are again possible number of games played by each team, but this time ranging from to .

- Since there are teams and still only possible number of games played, there must be teams that have played the same number of games. [By pigeonhole principle]

- Either way, there must be teams that have played the same number of games. [Proof by cases]